Schematically speaking, the works of Daphne Angelidou can be divided into three unities: “rural landscapes”, “cityscapes” and “Pediastrian Crossings”. In all three categories we find the same underlying “haunted world”, one that is almost transcendental due to the silence of the stones, both literally and figuratively, that possesses it. Frozen spaces, resolutely accomplished like the solidness of the dominant material that fashions them, namely marble and stone tesserae. Here time has turned to stone, endowing the works’ moment of plasticity with a sense of the perennial.

The unity “Pedestrian Crossings” is the only one in which the human figure appears. Be it a crowd or a solitary passer-by, loneliness and silence prevail in these scenes. Somber-colored figures in transit or at a standstill, they remain “directionless”. Almost all these personages hold colored umbrellas that cover their faces in such a way that the bright shades, although just “masks”, appear more vibrant than the people under them. The whole inspires the feeling that these people are ruled by a constant need for concealment, which is reinforced by the umbrella’s resemblance to a permanent “prosthesis” and not simply on hand to shelter them from a sudden downpour. In truth, these creatures lack inner protection and consequently cohesion, having assigned it to something on the exterior, an object. By extension, the streets where people and pedestrians circulate, as well as the façades of particular houses that delimit some of the streets, lose their vitality and they are transformed into stage design maquettes as a counterpoint to the figures who seem more like human cut-outs pasted on to the maquette.

Similarly, Angelidou’s “cityscapes” are transformed into stage-like landscape scenery with façades of manifestly empty houses, their stony silence abounding in absence. We could say that this space recalls the atmosphere of de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings in their endless expectation of an eventual human occurrence; a human performance that would transform the vacancy into plenitude. These façades like so many Sleeping Beauties of the City silently and steadfastly wait to be resuscitated by the kiss of life, almost as if they were aware that “time spent waiting is inanimate time”.

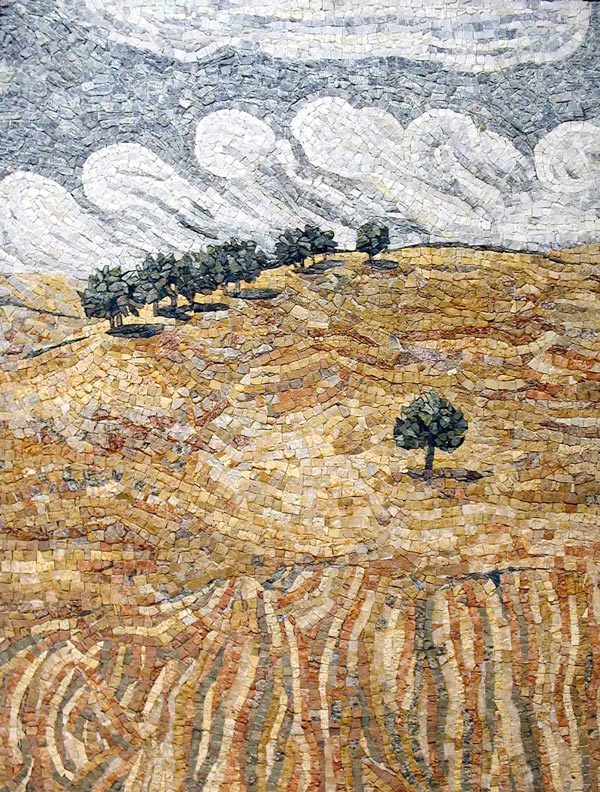

Lastly, the “rural landscapes”, scenes of Mani develop from an Impressionist bird’s-eye view suggestive of direct visual experience. In the foreground crop up rustic houses of which the uncertainty of the outlines where the abode meets the ground creates the illusion that they have sprouted from the soil. Before the houses nature unfurls. In this way, the earth appears to be the whole containing the house part. In other words the diachronic coexists with the instantaneous, the eternal with the ephemeral, God with man. All this transpires in the quietude, the vastness evoked by the works of Angelidou. Here the stone tesserae, like the stony structure of the houses, rejoin the rocky substance of Mani soil. And I would venture to say that what we seek in these works is not only forms in stone but stone as an amorphous material and one that intrinsically contains the energy necessary for it to take shape. This means that it is a live substance. It is in this direction that the landscapes guide my gaze with their precipitous tripartite partitions: at the bottom level the placement of tesserae evokes a tumultuous core like fire at the earth’s center. On the next, or median plane, the mosaic arrangement observes a certain regularity that is more virtual than definitive. This is the earth’s surface. Finally, the upper tier of air and clouds, that puts us in mind of Van Gogh’s landscapes, gives form to the same mobility of energy. Matter and energy structure the universe.In the end, Angelidou focuses on our surroundings, both natural and constructed. The natural environment seems more alive in the sense that its vitality is inherent. By contrast, the man-made environment is determined by human presence, one that is “lively” in appearance. In any case, the two human environments, both natural and constructed, where human presence is made palpable by its absence, stand before us expectantly. It would seem that here these two constitute the objective of the human quest – yet of a human being who is doubly lost, under his umbrella-shield and wandering in a disorienting white space like the lonely figures that people the artist’s recent works. After all, perhaps everything remains in a state of waiting, summoned by the universal need for invigorating encounters.

Andreas Ioannidis

Art Historian